The Quick Therapy That Actually Works

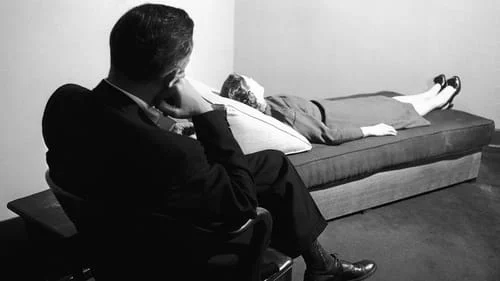

A doctor listens to a patient at the New York Psychoanalytic Institute Treatment Center in New York in 1956.BOB WANDS / AP

By: Olga Khazan

The strange little PowerPoint asks me to imagine being the new kid at school. I feel nervous and excluded, its instructions tell me. Kids pick on me. Sometimes I think I’ll never make friends. Then the voice of a young, male narrator cuts in. “By acting differently, you can actually build new connections between neurons in your brain,” the voice reassures me. “People aren’t stuck being shy, sad, or left out.”

The activity, called Project Personality, is a brief digital activity meant to build a feeling of control over anxiety in 12-to-15-year-olds. Consisting of a series of stories, writing exercises, and brief explainers about neuroscience, it was created by Jessica Schleider, an assistant professor at Stony Brook University, where she directs the Lab for Scalable Mental Health . She sent it to me so I could see how teens might use it to essentially perform psychotherapy on themselves, without the aid of a therapist.

In the middle of my new-kid scenario, the program tells me the story of Phineas Gage, the 19th-century railroad worker whose behavior changed radically after a metal spike was driven through his skull. With white backgrounds and rudimentary drawings, the program uses Gage’s experience to suggest that personality resides at least partly in the brain. If a metal spike can change your disposition, Project Personality reasons, so can something less violent—such as a shift in your mind-set. There are, perhaps, better ways to illustrate this than an extreme and hotly disputed historical event, but Project Personality finds a way to make it uplifting: “By learning new ways of thinking, each of us can grow into the type of person we want to be.”

Toward the end, the activity asks me to reassure a friend who was snubbed by another friend in high school. What would I tell the friend about how people can change? It encourages me to apply what I just learned about personality and the brain. The total program takes me less than an hour to complete.

Schleider admits that the production values are a little rudimentary; she’s currently working on a slicker version. Still, last year, she and her colleague John Weisz found that a single session with a very similar program helped reduce depression and anxiety among 96 young people ages 12 to 15. Beyond digital programs such as Project Personality, Schleider’s lab is about to test how well a single session of in-person psychotherapy can help teens and adults. The session will focus on “taking one step toward solving a problem that’s very troublesome,” she told me. “People will leave with a concrete plan for how to cope.”

If Schleider’s work is successful, it may help upend the traditional, pricey model of American psychotherapy. She wants to see whether people can get the same benefit from just an hour of digital or in-person therapy as they can from paying $200 an hour every week for months.

Granted, there are known risks to using well-meaning quick fixes as therapy. In one of her studies , Schleider points out that Scared Straight programs, in which teens visit with prisoners, are a type of single-session intervention, but they actually have been found to increase youth delinquency. There are also plenty of apps these days that allow people to access therapy-like programs without either an expensive psychologist or a primitive PowerPoint.

But Schleider argues that many wellness apps out there haven’t been proved to work. Her lab’s goal is to study the effectiveness of various programs, digital and in-person, to be sure that they’re doing what they’re supposed to. Effective solutions are crucial because Americans—stressed out, lonely, and ghosted by Tinder dates—are in desperate need of someone to talk to. The data suggest that most of the Americans who have a mental illness aren’t receiving treatment. About 30 percent of psychotherapists don’t take insurance. The wait list for the roster of therapists at Stony Brook’s community clinic , who take insurance and charge relatively lower fees, is three to six months. As Schleider put it to me, her quick interventions offer “something, when the alternative is nothing.”

Single-session interventions, like the kind Schleider studies, are typically five to 90 minutes long and, eventually, could be deployed in schools or pediatricians’ offices, rather than in traditional therapists’ offices. Schleider’s lab is especially interested in targeting adolescents, since about half of all mental illnesses set in by age 14. Unlike traditional therapy, Schleider’s program and others aim to get participants to become “helpers” for their peers after they’ve learned information about personality change for themselves. The point is to increase intrinsic motivation: Kids might be more likely to want to sort out other kids’ problems than to sit in their room and do therapy homework.

Perhaps to the chagrin of those of us who have sunk entire paychecks into traditional psychotherapy, there is some evidence that extremely brief therapy is indeed effective. Schleider published a meta-ana lysis of single-session interventions focused on children and teens (not including her own work, which was tested later) that found that a teen who received a single-session intervention had a 58 percent greater chance of having his or her symptoms improve than one who did not. The single sessions worked especially well for decreasing anxiety and behavioral problems. In fact, Schleider says, on these measures, one session of therapy turned out to be about as effective as 16 sessions. “I don’t know if that’s great or scary,” she says.

Other researchers have also discovered some surprising benefits to quick interventions. One study found that just four days of exposure therapy—in which patients confront whatever they are preoccupied with—helped two-thirds of teens with obsessive-compulsive disorder go into remission. A separate 90-minute intervention increased college students’ sense of “hope, life purpose, and vocational calling.” And a somewhat longer-term program of four to eight weeks was enough to change a person’s personality. That’s longer than 90 minutes, but it’s shorter than many traditional psychotherapy regimens, which can be open-ended and go on for years.

“Definitely, there are times when one session can be powerful,” says Michael Brustein, a clinical psychologist in Manhattan. One fast-acting technique he mentions is motivational interviewing, in which the therapist prods the patient to examine whether his actions are helping him achieve his goals. For example, a father who missed his son’s basketball game because of a drinking problem might be asked whether he’s living up to his sense of what it means to be a “good father.” Certain phobias can also be dealt with in a few short consultations: Brustein told me he once helped a yoga instructor manage an elevator phobia by applying mindfulness techniques from his yoga practice.

Shorter-term therapy is also more likely to work if your definition of “work” isn’t “become permanently and totally happy.” “For too long, our target has been total amelioration of symptoms,’” Jodi Polaha, a psychologist and East Tennessee State University professor, told me via email. (Polaha researches therapeutic interventions that are as short as 20 minutes and delivered in a doctor’s office; I profiled her clinic in 2017.) Rather than complex mental illnesses, simpler problems—such as smoking cessation, weight loss, and even medication adherence—might yield to the precision strike of a short intervention, Polaha said.

The big challenge to scaling up this kind of microtherapy, according to Polaha, is convincing both patients and doctors that there’s no special transformation that happens at 50 minutes. “When I start sessions with my patients, I always tell them we will talk for 30 minutes and then decide if follow-up is needed,” she said, “because change can happen at any time.”

Lynn Bufka, a psychologist with the American Psychological Association, says that these types of brief interventions could be just a first step toward the treatment of various mental-health woes. They might be enough for some people, while others go on to get more intensive therapy. But Brustein and Bufka both say that for more severe issues, such as bipolar disorder and major depression, a quick dose of therapy is unlikely to be enough. “These kinds of interventions are probably more likely to be beneficial before full-blown symptoms or disorders have developed,” Bufka told me.

If Schleider succeeds, and the air begins to leak out of the 50-minute, weekly therapy model, we may begin to wonder: What is the point of therapy? For decades, Americans have been told that the key to inner tranquility is to talk to someone. Have you tried cognitive-behavioral therapy? is the cop-out solution of stumped advice columnists everywhere. But how can talking to a stranger (or looking at a slide deck) for less than the length of a superhero movie be enough to fix your brain? What are we after when we go to therapy, anyway?

The fact that the short-term interventions span about the length of a movie is actually relevant, based on a metaphor Brustein used to describe the benefit of therapy. When you go to a movie, he noted, you can see the characters and understand their motivations. You can tell when they’re about to make a mistake: You wish you could scream at them to not go down to the basement, or back to that guy. But when it comes to our own lives, we have a harder time seeing those patterns. We’re too close to our own problems, so the basement seems like the perfect place to run to. One major goal of therapy, Brustein said, “is to observe ourselves from the outside.”

Therapists, like the anonymous narrator of Project Personality, aim to send a message: Your story isn’t over till it’s over. Your character’s plot is still unfolding; there’s still time to escape. Sometimes, it can take hours and hours on a therapist’s couch to understand that. Maybe, just maybe, it could start to take less.

Can You Solve All Your Problems in a Single Session of Therapy?

In less than two hours, you can get a tune-up and oil change, a tax refund, or a massage—and maybe a new outlook on life. That's the idea behind single-session therapy (SST), a method of counseling in which you show up, talk, listen, learn and leave, possibly forever. "In SST, the therapist and the client approach the meeting as though it will likely be the only one," says Michael F. Hoyt, PhD, who literally helped write the book on this brief but meaningful kind of therapy—indeed, he's coedited two volumes on the topic.

Hoyt isn't the only one who believes a single session can do the job. In her popular podcast, Where Should We Begin? , couples therapist and best-selling author Esther Perel makes significant headway against decades-long relationship problems in three-hour stand-alone sessions. In addition, "talk-in" clinics, which provide walk-in counseling for youths and their families or caregivers, are catching on in Canada, and therapists in the UK and Australia advertise their single-session expertise.

Hoyt didn't set out to specialize in quickies. He's a clinical psychologist originally trained in psychodynamic psychotherapy, which usually involves regular sessions over the course of months or years. But in the late 1980s, he was working with fellow psychologist Moshe Talmon, PhD, at an HMO in Northern California, when Talmon noticed that many of their patients came into the clinic only once. Along with psychologist Robert Rosenbaum, PhD, Hoyt and Talmon decided to follow up with 200 of these patients to ask why. "We were surprised to hear that the great majority felt like they got what they needed," says Hoyt. And this wasn't unique to their clinic: Other research showed that 20 to nearly 60 percent of those who visited a therapist went only once. So the trio did a study with 58 patients, in which they structured every first session as if it would be the last; 59 percent left feeling satisfied with their treatment and declined additional appointments, and of these one-and-done patients, 88 percent reported improvement three months later in the complaint they'd come to address. The researchers then developed guidelines for how to reframe a typical session based on the assumption that the patient wouldn't be back.

In 1988, Hoyt, Talmon and Rosenbaum presented their findings at a psychology conference in San Francisco. While some critics called SST "Band-Aid therapy," Holt says that many practitioners were intrigued by a method that could help large numbers of people while freeing up time for those requiring extended attention. As more professionals practiced SST, follow-up questionnaires showed that not only were patients getting a lot out of their session, but solving one problem led to improvement in other areas of their lives.

So, how does it typically work? In appointments that average 60 to 90 minutes, the therapist focuses on your strengths and skills, then helps you identify and practice things you can do now to get yourself unstuck. SST uses principles similar to cognitive-behavioral and solution-focused therapies, both of which are intended to help you fix your problem yourself. "Rather than looking at what negative thoughts and behaviors might be causing your issue, we look at what positive ones could solve it," says Hoyt.

That method strongly appealed to Keren, one of Talmon's recent patients in Israel. Though Keren is 48, married, and the mother of adult children, her parents were still trying to control her finances. But she wasn't interested in a deep analysis of the past; she wanted specific advice on how to talk to her parents about an issue that had been torturing her for some time: putting the house they had purchased and she lived in into her name. She worried that even broaching this subject could damage their relationship.

After 30 minutes with Talmon, Keren felt like he fully understood her family dynamic; they spent the second half of the session focusing on the imminent conversation and role-playing. "Dr. Talmon helped me see that not only had I been depending on my parents, but they were depending on me, too," Keren says. She also realized that her reaction to her parents' response—as bad as it might be—was completely in her hands. Two days after the session, Keren sat down with her mother alone and expressed how at this point in her life, not having the property in her name put her at a disadvantage. To her surprise, her mother agreed. "She said she'd never thought about it that way." Within three weeks, her parents presented her with a legal letter saying the property was hers. Keren doesn't plan to talk to Talmon about her parents again—but she did make an appointment to discuss a totally different issue involving her boss.

People who tend to do best with SST, Hoyt says, can identify a relatively specific goal: dealing with grief, building self-esteem, validating feelings. In studies, SST has also been shown to help reduce anxiety, recurring nightmares, alcohol abuse and self-harm, as well as help manage phobias and panic attacks. (Of course, there may be cases, as when someone has been abused or is dealing with trauma, when a single session "might open a can of worms and leave the client with feelings they can't handle," says Ryan Howes, PhD, a clinical psychologist in private practice in Pasadena, California, who has done a handful of one-off sessions at patients' request. Those cases are when additional sessions make sense. And Hoyt even says SST could be called "making the most of each visit" therapy, but, he admits, "that's not as catchy.")

The suggestion that you could solve a problem right here, right now, today, can be empowering. "The most common number of therapy visits many people commit to is zero," says Brian Yates, PhD, a professor of psychology at American University in Washington, D.C., who studies the cost-effectiveness of therapy. So if someone tries one visit and comes away with a concrete plan, a referral, or even the desire to attend more sessions, "that can be a whole lot better than nothing."

And in the end, says Talmon, "no matter how many sessions you need, if you approach each one as though it's the only one, it's likely to be the most cost-effective form of therapy you'll ever have."

Can We Talk?

While there's no SST directory to help you find a provider, you can check therapists' websites for phrases like "short term," "brief therapy," "solution-focused" and "problem-solving"; call these providers and ask if they're open to meeting once or a few times. You can also experience a de facto form of SST if you have access to an Employee Assistance Program (EAP) that offers free short-term counseling to employees with personal or work-related problems. Even if EAP counselors have never heard of SST, they know that each session could be the only one they'll have with a client, so they make it as useful as possible, says Janet Schirtzinger, EAP manager of clinical services at Advocate Aurora Health, which offers EAPs to companies in the Midwest.

From the May 2018 issue of O, The Oprah Magazine

Reference